KIDNEY STONES

Kidney stones, one of the most painful of the urologic disorders, have beset humans for centuries. Scientists have found evidence of kidney stones in a 7,000-year-old Egyptian mummy. Unfortunately, kidney stones are one of the most common disorders of the urinary tract. Each year, people make almost 3 million visits to health care providers and more than half a million people go to emergency rooms for kidney stone problems.

Many kidney stones pass out of the body without any intervention. Stones that cause lasting symptoms or other complications may be treated by various techniques, most of which do not involve major surgery. Also, research advances have led to a better understanding of the many factors that promote stone formation and thus better treatments for preventing stones.

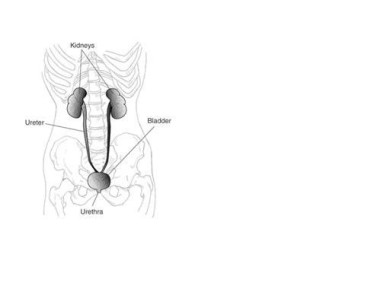

Introduction to the Urinary Tract

The urinary tract, or system, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The kidneys are two bean-shaped organs located below the ribs toward the middle of the back, one on each side of the spine. The kidneys remove extra water and wastes from the blood, producing urine. They also keep a stable balance of salts and other substances in the blood. The kidneys produce hormones that help build strong bones and form red blood cells.

The urinary tract.

Narrow tubes called ureters carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder, an oval-shaped chamber in the lower abdomen. Like a balloon, the bladder's elastic walls stretch and expand to store urine. They flatten together when urine is emptied through the urethra to outside the body.

What is a kidney stone?

A kidney stone is a hard mass developed from crystals that separate from the urine within the urinary tract. Normally, urine contains chemicals that prevent or inhibit the crystals from forming. These inhibitors do not seem to work for everyone, however, so some people form stones. If the crystals remain tiny enough, they will travel through the urinary tract and pass out of the body in the urine without being noticed.

Kidney stones may contain various combinations of chemicals. The most common type of stone contains calcium in combination with either oxalate or phosphate. These chemicals are part of a person's normal diet and make up important parts of the body, such as bones and muscles.

A less common type of stone is caused by infection in the urinary tract. This type of stone is called a struvite or infection stone. Another type of stone becoming more common are uric acid stones, and cystine stones are rare.

Urolithiasis is the medical term used to describe stones occurring in the urinary tract. Other frequently used terms are urinary tract stone disease and nephrolithiasis. Doctors also use terms that describe the location of the stone in the urinary tract. For example, a ureteral stone-or ureterolithiasis-is a kidney stone found in the ureter.

Gallstones and kidney stones are not related. They form in different areas of the body. Someone with a gallstone is not necessarily more likely to develop kidney stones.

Who gets kidney stones?

For uncertain reasons, the number of people with kidney stones has been increasing over the past 30 years. Stones occur more frequently in men. The prevalence of kidney stones rises dramatically as men enter their 40s and continues to rise into their 70s. For women, the prevalence of kidney stones peaks in their 50s. Once a person gets more than one stone, other stones are likely to develop.

What causes kidney stones?

We do not always know what causes a stone to form. While certain foods may promote stone formation in people who are susceptible, scientists do not believe that eating any specific food causes stones to form in people who are not susceptible.

A person with a family history of kidney stones may be more likely to develop stones. Urinary tract infections, kidney disorders and anatomical variations, and certain metabolic disorders such as hyperparathyroidism are also linked to stone formation.

In addition, more than 70 percent of people with a rare hereditary disease called renal tubular acidosis develop kidney stones.

Cystinuria and hyperoxaluria are two other rare, inherited metabolic disorders that often cause kidney stones. In cystinuria, too much of the amino acid cystine, which does not dissolve in urine, is voided, leading to the formation of stones made of cystine. In patients with hyperoxaluria, the body produces too much oxalate, a salt. When the urine contains more oxalate than can be dissolved, the crystals settle out and form stones.

Hypercalciuria is inherited, and it may be the cause of stones in more than half of patients. Calcium is absorbed from food in excess and is lost into the urine. This high level of calcium in the urine causes crystals of calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate to form in the kidneys or elsewhere in the urinary tract.

Other causes of kidney stones are hyperuricosuria, which is a disorder of uric acid metabolism; gout; excess intake of vitamin D; urinary tract infections; and blockage of the urinary tract. Certain diuretics, commonly called water pills, and calcium-based antacids may increase the risk of forming kidney stones by increasing the amount of calcium in the urine.

Calcium oxalate stones may also form in people who have chronic inflammation of the bowel or who have had an intestinal bypass operation, or ostomy surgery. As mentioned earlier, struvite stones can form in people who have had a urinary tract infection. People who take the protease inhibitor indinavir, a medicine used to treat HIV infection, may also be at increased risk of developing kidney stones.

Foods and Drinks Containing Oxalate

People prone to forming calcium oxalate stones may be asked to limit or avoid certain foods if their urine contains an excess of oxalate.

High-oxalate foods-higher to lower

rhubarb

spinach

beets

swiss chard

wheat germ

soybean crackers

peanuts

okra

chocolate

black Indian tea

sweet potatoes

Foods that have medium amounts of oxalate may be eaten in limited amounts.

Medium-oxalate foods-higher to lower

grits

grapes

celery

green pepper

red raspberries

fruit cake

strawberries

marmalade

liver

Source: The Oxalosis and Hyperoxaluria Foundation.

What are the symptoms of kidney stones?

Kidney stones often do not cause any symptoms. Usually, the first symptom of a kidney stone is extreme pain, which begins suddenly when a stone moves in the urinary tract and blocks the flow of urine. Typically, a person feels a sharp, cramping pain in the back and side in the area of the kidney or in the lower abdomen. Sometimes nausea and vomiting occur. Later, pain may spread to the groin.

If the stone is too large to pass easily, pain continues as the muscles in the wall of the narrow ureter try to squeeze the stone into the bladder. As the stone moves and the body tries to push it out, blood may appear in the urine, making the urine pink. As the stone moves down the ureter, closer to the bladder, a person may feel the need to urinate more often or feel a burning sensation during urination.

If fever and chills accompany any of these symptoms, an infection may be present. In this case, a person should contact a doctor immediately.

How are kidney stones diagnosed?

Sometimes "silent" stones-those that do not cause symptoms-are found on x rays taken during a general health check. If the stones are small, they will often pass out of the body unnoticed. Often, kidney stones are found on an x ray or ultrasound taken of someone who complains of blood in the urine or sudden pain. These diagnostic images give the doctor valuable information about the stone's size and location. Blood and urine tests help detect any abnormal substance that might promote stone formation.

Imaging of the urinary system using a special test called a computerized tomography (CT) scan or an intravenous pyelogram (IVP) helps to determine the proper treatment.

Preventing Kidney Stones

A person who has had more than one kidney stone may be likely to form another; so, if possible, prevention is important. To help determine their cause, laboratory tests, including urine and blood tests can be ordered. A patient's medical history, occupation, and eating habits are also important. If a stone has been removed, or if the patient has passed a stone and saved it, a stone analysis by the laboratory may help in planning treatment.

It may be necessary to collect urine for 24 hours after a stone has passed or been removed. The collection is used to measure urine volume and levels of acidity, calcium, sodium, uric acid, oxalate, citrate, and creatinine-a product of muscle metabolism. The doctor will use this information to determine the cause of the stone. A second 24-hour urine collection may also be needed and further repeats can determine whether the prescribed treatment is working.

How are kidney stones treated?

Fortunately, surgery is not always necessary. Many kidney stones can pass through the urinary system with plenty of water-2 to 3 litres a day-to help move the stone along. Often, the patient can stay home during this process, drinking fluids and taking pain medication as needed. Any stone passed can be sent for testing. It can be caught in a cup or tea strainer used only for this purpose.

Lifestyle Changes

A simple and most important lifestyle change to prevent stones is to drink more liquids-water is best. Someone who tends to form stones should try to drink enough liquids throughout the day to produce at least 2 litres of urine in every 24-hour period.

In the past, people who form calcium stones were told to avoid dairy products and other foods with high calcium content. Recent studies have shown that foods high in calcium, including dairy products, may help prevent calcium stones. Taking calcium in pill form, however, may increase the risk of developing stones.

Patients may be told to avoid food with added vitamin D and certain types of antacids that have a calcium base. Someone who has highly acidic urine may need to eat less meat, fish, and poultry. These foods increase the amount of acid in the urine.

To prevent cystine stones, a person should drink enough water each day to dilute the concentration of cystine that escapes into the urine, which may be difficult. More than a gallon of water may be needed every 24 hours, and a third of that must be drunk during the night.

Medical Therapy

Certain medications may help prevent calcium and uric acid stones. These medicines control the amount of acid or alkali in the urine, key factors in crystal formation. The medicine allopurinol may also be useful in some cases of hyperuricosuria.

It is possible to control hypercalciuria, and thus try to prevent calcium stones, by prescribing certain diuretics, such as thiazides. These medicines decrease the amount of calcium released by the kidneys into the urine by favoring calcium retention in bone. They work best when sodium intake is low. However, not all patients tolerate such medicines.

If cystine stones cannot be controlled by drinking more fluids, a doctor may prescribe a medicines such as Thiola, which helps to reduce the amount of cystine in the urine.

For struvite stones that have been totally removed, the first line of prevention is to keep the urine free of bacteria that can cause infection. A patient's urine will be tested regularly to ensure no bacteria are present.

People with hyperparathyroidism sometimes develop calcium stones. Treatment in these cases is usually surgery to remove the parathyroid glands, which are located in the neck. In most cases, only one of the glands is enlarged. Removing the glands cures the patient's problem with hyperparathyroidism and kidney stones.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery may be needed to remove a kidney stone if it does not pass after a reasonable period of time and causes constant pain, is too large to pass on its own or is caught in a difficult place and blocks the flow of urine or causes an ongoing urinary tract infection, damages kidney tissue or causes constant bleeding or has grown larger, as seen on follow-up x rays.

Until 20 years ago, open surgery was necessary to remove a stone. The surgery required a recovery time of 4 to 6 weeks. Today, treatment for these stones is greatly improved, and many options do not require major open surgery and can be performed in an outpatient setting.